Thanksgiving, 1981. I’m in Leipzig, Germany for the Leipzig International Documentary and Short Film Festival. At the time, I was a PhD. candidate at the University of Münster in the Federal Republic of Germany, which offered a fellowship and no tuition. But going to Leipzig in the winter on a train is a trip. The train is crowded with workers who eye me suspiciously, seeing me in what are obviously western clothes. We are still in the old German Democratic Republic (GDR), a Stalinist dictatorship that was neither a republic nor democratic.

There is a little drama after my arrival in Leipzig from East Berlin. Apparently, despite my showing my official invitation letter to the Festival to the passport officials at Checkpoint Charlie—the only official Allied entry point into East Germany—I had only been given a visa for East Berlin. At the time, through a twist in logic that could only come from communist bureaucracies, Berlin (Ost) was both the “Capital City of the German Democratic Republic” and extra-territorial, necessitating a completely different visa for Leipzig. I was therefore an “illegal.” Thankfully, Manfred Lichtenstein from the State Film Archives of the GDR, a colleague I had previously met, went to the authorities and got things fixed, without me having to spend time in an East German gulag. Years later, after the Wall came down, I found out that Lichtenstein had been the Stasi guy at the Archive. Not just an “unofficial informant,” as they were called, but an officer. I didn’t know that then, but no one else would have had the rank to save my butt.

Thanksgiving fell on November 26 that year, or so my diary tells me. There’s snow on the ground and a Christmas market where they sell hot spiced wine, which is not a whole lot different from similar markets in über-Catholic Münster. Not even the Sozialistische Einheitspartei (Socialist Unity Party) could ban Christmas. There did, however, seem to be a lot fewer stores around. In the morning, I head over to the cinema where they are showing the retrospective, “American Social Documentary - USA-Documentary films 1930-1945,” and see Leo Hurwitz’s Dialogue with a Woman Departed (1981), followed by some Workers Film and Photo League newsreels from the 1930s that Hurwitz had worked on.

I don’t remember how I got it, but I received an invitation to a Thanksgiving dinner from Anne and Will Roberts, documentary filmmakers from Athens, Ohio. So, in the early evening I make my way to Auerbach’s Keller, where a table has been reserved. Yes, the very same Auerbach’s Cellar where Goethe did some serious drinking, memorializing the location in “Faust, Part I,” when Faust watches Mephisto use magic to play with the local yokels. They don't have turkey, only duck with dumplings and apple sauce. We make due.

"But what had tied us together for a brief moment was that we were Americans, expats and otherwise, celebrating a uniquely American holiday, even as we were strangers in a strange land, in search of a family."

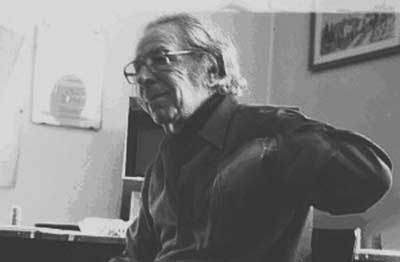

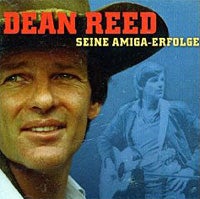

Will Roberts was at the time in pre-production on a documentary about an American singer who had become a film and singing star in the GDR, Dean Reed. The film was released in 1985, American Rebel: The Dean Reed Story, a year before Reed passed away. So Dean Reed and the Roberts were at the table, along with several American guests. Reed had on a cowboy shirt, and I did think it odd that he would want to live in East Germany of his own free will, but then again, I didn’t really understand what a huge star he was in Moscow and other points East. Another guest was Leo Hurwitz, whose films I had seen earlier in the day, and had also co-directed Native Land (1942) with Paul Strand, a film I knew well. Leo was seventy-two at the time and still full of piss and vinegar, at least as far as his politics were concerned. Forever the historian, I spent much of the evening talking to Leo, who had cut sections of Native Land into his new film, which I thought was a wonderfully poetic and utterly romantic view of left-wing politics. At 225 minutes, it was also really, really long. I sometimes wonder what happened to the film after Leo passed. After the dinner, I went back to watch U.S. Office of War Information movies at the retrospective and I never saw any of my tablemates again. But what had tied us together for a brief moment was that we were Americans, expats and otherwise, celebrating a uniquely American holiday, even as we were strangers in a strange land, in search of a family.

Will Roberts was at the time in pre-production on a documentary about an American singer who had become a film and singing star in the GDR, Dean Reed. The film was released in 1985, American Rebel: The Dean Reed Story, a year before Reed passed away. So Dean Reed and the Roberts were at the table, along with several American guests. Reed had on a cowboy shirt, and I did think it odd that he would want to live in East Germany of his own free will, but then again, I didn’t really understand what a huge star he was in Moscow and other points East. Another guest was Leo Hurwitz, whose films I had seen earlier in the day, and had also co-directed Native Land (1942) with Paul Strand, a film I knew well. Leo was seventy-two at the time and still full of piss and vinegar, at least as far as his politics were concerned. Forever the historian, I spent much of the evening talking to Leo, who had cut sections of Native Land into his new film, which I thought was a wonderfully poetic and utterly romantic view of left-wing politics. At 225 minutes, it was also really, really long. I sometimes wonder what happened to the film after Leo passed. After the dinner, I went back to watch U.S. Office of War Information movies at the retrospective and I never saw any of my tablemates again. But what had tied us together for a brief moment was that we were Americans, expats and otherwise, celebrating a uniquely American holiday, even as we were strangers in a strange land, in search of a family.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation