Most film historians today consider Konrad Wolf and Rainer Werner Fassbinder the two greatest German filmmakers in the latter half of the 20th Century. Fassbinder grew up in Munich, in the American Zone of Occupation, and made films that paid homage to American genre cinema; while Wolf worked in what was then called the German Democratic Republic (GDR)—in reality a Stalinist dictatorship—yet he was able to produce films that were complex meditations on the ambiguities of life. Tragically, both died young. Fassbinder at 37, Wolf at 56, both in 1982. I’ve had a soft spot in my heart for both directors. Fassbinder, because I published my very first article, a review in The Village Voice, on his Ali – Fear East the Soul (1974); Wolf, because he was born in the same year as my German mother and died within months of her passing.

I first became aware of Konrad Wolf at the Berlin Film Festival in 1977, where his film, Mama, I’m Alive (1977), was shown to much acclaim. It is a fictionalized, autobiographical version of his service in the Red Army during World War II, fighting the German Wehrmacht to liberate his homeland from the Nazis. However, it wasn’t until seeing a documentary about his life at the Leipzig Film Festival in November 1982 that I realized what a perfect biography he had as star filmmaker in the GDR.

I first became aware of Konrad Wolf at the Berlin Film Festival in 1977, where his film, Mama, I’m Alive (1977), was shown to much acclaim. It is a fictionalized, autobiographical version of his service in the Red Army during World War II, fighting the German Wehrmacht to liberate his homeland from the Nazis. However, it wasn’t until seeing a documentary about his life at the Leipzig Film Festival in November 1982 that I realized what a perfect biography he had as star filmmaker in the GDR.

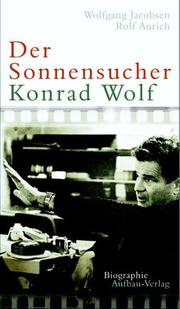

My bedtime reading over the past several months has been Der Sonnensucher. Konrad Wolf (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2005), an excellent and moving, close-to-600-page biography, published in Germany by Wolfgang Jacobsen and Rolf Aurich. His was a remarkable journey.

My bedtime reading over the past several months has been Der Sonnensucher. Konrad Wolf (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2005), an excellent and moving, close-to-600-page biography, published in Germany by Wolfgang Jacobsen and Rolf Aurich. His was a remarkable journey.

Born in Stuttgart in 1925, Konrad Wolf was one of two sons of Friedrich Wolf, one of the most famous playwrights in Weimar, Germany; the author of “Cyankali” (1929), a pro-choice drama about a working class girl who dies after a botched illegal abortion; and, like Bertolt Brecht, a Communist sympathizer. Konrad Wolf’s brother, Markus, later became the head of East German espionage, master-minded the use of female sex spies in countless European capitals and helped bring down the government of Chancellor Willy Brandt in 1974.

Being German Jews, the family fled to the Soviet Union in 1933, where Wolf grew up as a Russian citizen, attending both German and Russian language schools in Moscow. His identity was neither completely Russian, nor German. I could relate: At the age of 13, I moved to West Germany with my parents, an American kid suddenly thrust into an alien environment. After this childhood trauma of displacement, we were both forever crossing borders, never quite at home on one side or the other.

"After this childhood trauma of displacement, we were both forever crossing borders, never quite at home on one side or the other."

In 1944, at the age of 19, Wolf joined the Red Army and had to fight German soldiers, some of whom he had once sat next to in school. Jacobsen and Aurich do a great job of describing the conflicting feelings of ambiguity, uncertainty, and also emotional pain the young Wolf experienced. Unlike his brother, a Realpolitiker beholden to power more than principles, Wolf agonized over his split identity. At the end of the War, just twenty years old, he helped rebuild a denazified German cultural life as an officer in the Soviet Army of occupation. This was not an easy job, especially given that the ordinary Germans he dealt with on a daily basis considered him a traitor. In his own mind, however, he was fighting for an anti-Fascist and democratic future, still painfully unaware that the German Communists under Walter Ulbricht, including his older brother Markus, had a very different vision for Germany.

In 1944, at the age of 19, Wolf joined the Red Army and had to fight German soldiers, some of whom he had once sat next to in school. Jacobsen and Aurich do a great job of describing the conflicting feelings of ambiguity, uncertainty, and also emotional pain the young Wolf experienced. Unlike his brother, a Realpolitiker beholden to power more than principles, Wolf agonized over his split identity. At the end of the War, just twenty years old, he helped rebuild a denazified German cultural life as an officer in the Soviet Army of occupation. This was not an easy job, especially given that the ordinary Germans he dealt with on a daily basis considered him a traitor. In his own mind, however, he was fighting for an anti-Fascist and democratic future, still painfully unaware that the German Communists under Walter Ulbricht, including his older brother Markus, had a very different vision for Germany.

Wolf, after studying at the famous Moscow film school where Sergei Eisenstein was an instructor (Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography), began directing films in 1954 in Babelsberg, the old UFA studios, which had since morphed into the East German DEFA Studios. His third film, Lissy (1957), was about a German working class woman whose husband becomes a Nazi out of opportunism in 1933, while her brother is executed. His next remarkable film, Sonnensucher (1957/1972), portrayed the conflicts between German uranium miners and their Russian masters, and was promptly banned for fifteen years.

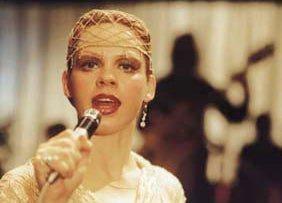

All his films, e.g. The Divided Heaven (1964), Goya (1971) or Solo Sunny (1981), the latter about a girl wanting to be a punk rock star in a Communist State that still banned rock and roll, are about deeply conflicted characters, facing difficult moral choices, hardly the stuff of film propaganda. Yet after his death, the East German communist propaganda machine tried to turn him into the embodiment of Russian-German friendship. That chimera only lasted a few more years until the Wall came down in 1989, after which Konrad Wolf was rehabilitated for what he really was, an artist of great humanity.

All his films, e.g. The Divided Heaven (1964), Goya (1971) or Solo Sunny (1981), the latter about a girl wanting to be a punk rock star in a Communist State that still banned rock and roll, are about deeply conflicted characters, facing difficult moral choices, hardly the stuff of film propaganda. Yet after his death, the East German communist propaganda machine tried to turn him into the embodiment of Russian-German friendship. That chimera only lasted a few more years until the Wall came down in 1989, after which Konrad Wolf was rehabilitated for what he really was, an artist of great humanity.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation