Peter Decherney’s new book, "Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet" (2012), is a groundbreaking study on what has been an understudied aspect of American film history, namely film copyright. Decherney takes a well-established history of Hollywood and turns it on its head to reveal the way copyright has influenced many of the turns that the movie industry has taken.

Peter’s first chapter on the many copyright battles in the cinema’s first 20 years is particularly illuminating, because he utilizes previously hidden documents, such as case law records, to construct a very different narrative of film’s early development from the one-shot films of the 1890s to full-blown feature films in 1915. Indeed, the technological and aesthetic evolution of moving pictures is much more dependent on the establishment of court precedents than anyone had ever previously realized with Decherney illustrating the symbiotic relationship between media technology and the law.

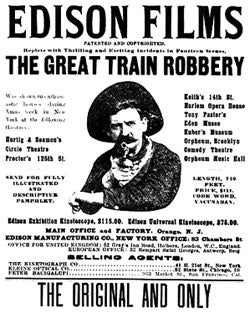

To my knowledge, no academic film historian has crafted such a legalistic perspective, nor has anyone highlighted with quite the same urgency the central role that piracy played in early cinema and its popularization. Yes, I remember seeing the Lubin and Porter versions of The Great Train Robbery (1903), but I wasn’t aware of the fact that piracy was part of the business model of the first generation of American filmmakers.

"Yes, I remember seeing the Lubin and Porter versions of The Great Train Robbery (1903), but I wasn’t aware of the fact that piracy was part of the business model of the first generation of American filmmakers."

In his second chapter, Decherney demonstrates the way American courts took material essentially in the public domain and privatized it, as the film industry developed an economy in which their contract actors’ value had to be protected by law. And it is case law, so argues Decherney, that defines the power to control all media, turning a chaotic cottage industry into a well-functioning monopoly.

In the following chapters, Decherney confronts the technological revolutions of television, home video, and the digital Internet, chapters in which the former pirates (Hollywood) accuse their younger competitors of piracy and copyright infringement. The advent of television in fact benefitted greatly from film and radio’s accumulation of media case law. Likewise, the battle over artists' rights when Hollywood filmmakers organized to oppose colorization and reformatting for video formats. Finally, the courts will ultimately establish the parameters of moving image distribution via the Internet, as Decherney theorizes in his final chapter.

Peter Decherney’s copyright book is not only groundbreaking, but will catapult him into the first rank of film scholars. Film scholars tend to shy away from difficult texts outside their field, so Peter took on a huge task in learning how to master American case law in regard to copyright without being a lawyer. It is his ability to read those texts and make them legible to the field of film studies that makes his work original. Furthermore, Decherney’s book will cause a seismic shift in our film historical thinking regarding the primary motors of the development of cinema. It opens up many other avenues of inquiry—most directly, the relationship between case law and the development or suppression of film technology; law and the economic development of the media industry, beyond milestone cases like the Paramount Consent Decree; law enforcement and audience control through censorship, etc.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation