The Film Studies Department of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, recently invited a little more than 20 film academics, the great majority graduate students, to a symposium, “Das Nachkriegskino in Deutschland: Reflexionen des beschädigten Lebens?,” which translates as “German Post-War Cinema: Reflections of Damaged Lives.”

Organized by Imme Klages, Bastian Blachut and Sebastian Kuhn, all doctoral candidates working under Prof. Vinzenz Hediger in Frankfurt, the group theorized that the immediate post-war German Cinema, despite some recent revisionist texts, still suffered from critical neglect. Despite its status as a highly successful commercial cinema (at least in the domestic sphere), it failed to make any impact abroad, and also got a bad rap from the New German Cinema generation of the 1960s and 1970s, which put it down as “Pappa’s Kino.” Taking their cues from Anton Kaes’ groundbreaking "Shell Shock Cinema," and without necessarily trying to rehabilitate German film production from 1945 to 1960, the symposium’s organizers suggested that it was time to look at the breaks and empty spaces, brought about by the repression of the immediate Nazi past, the failure of denazification, the exile and mass murder of a whole generation of (Jewish) filmmakers after 1933 and the lack of a critical documentary tradition.

Indeed, as a site of collective repression, German post-war cinema supported a “forgetting without images,” in the words of Klaus Kreimeier. In this respect, East and West German cinema differed little. In the former German Democratic Republic, the Communist Party invented a collective imaginary in its state-produced films that connected the political system to the revolutionary successes of the German Socialists in the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic, while denying all culpability for the Third Reich and the Shoah. However, as one speaker noted, that strategy was always in danger of backfiring, because the Communist came to power not through a legitimate revolution from below, but through Soviet occupation from above. Another participant demonstrated the way a film like Council of the Gods (1950) allowed the GDR to place all blame on big capitalists, who of course all lived in West Germany. Finally, even the DEFA, as the state film monopoly was named, produced escapist musicals, far from any reality.

Meanwhile, in West Germany, the privately financed film industry cranked out endless series of genre films, including “Heimatfilms” (a unique German genre akin to modern westerns), musical films, melodramas and comedies. Produced in the Nazi-perfected UFA style, these genres enjoyed tremendous box office, at least until the audience migrated to television in the late-1950s. To measure Germany’s post-war traumas, then, numerous speakers pointed out what was not articulated or only implied between the lines, in this cinema of pure escapism: the Nazi concentration camps, the German fascist war of aggression, the bombing of German cities, the hoards of ethnic German refugees from Eastern Europe, the starving millions in the winter of 1947, the war crimes trials, denazification and its rapid abandonment by the Allies, etc.

Ironically, after 1945 it had all seemingly started out differently. The so-called “Trümmerfilms” not only visualized the ruins (both architectural and human), but also named war criminals, as several analyses of The Murders Are Among Us (1946) demonstrated. But as others pointed out, the “rubble films” also employed strategies of displacement to deny any collective guilt for the millions of dead, while individual guilt dissipated in narratives that blamed the Nazi system or ended in suicides that turned perpetrators into victims. The mythical “Zero Hour” of German cinema was further relativized by the fact that these films were produced almost exclusively by former Nazi filmmakers, in the UFA style, rather than in the neorealist style that characterized post war Italian cinema. Even Roberto Rossellini’s Germania Anno Zero (1947), which ends in the suicide of an innocent young boy, could not escape such mechanisms, while American documentaries, like The Death Mills (1945) with its mountains of corpses, were perceived by the Germans to be pure propaganda. Images of the Holocaust thus quickly disappeared into the archives, while Hollywood anti-Nazi films, like Berlin Express (1948), were either never shown in the Federal German Republic or had their plots rewritten to turn Nazis into drug smugglers.

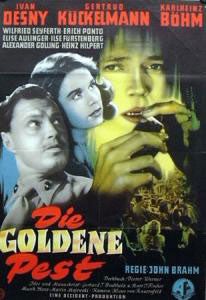

German cinema in the 1950s, then, seems at first glance to exist eons from contemporary reality. However, a second look reveals fissures in the happy edifice, e.g. the comedian Heinz Erhardt, who played symbolically castrated authority figures, or the many refugees at the plot margins of Heimatfilms. Or dramas like Roses for the Prosecutor (1959), in which a state’s attorney is revealed to have been a Nazi judge, handing out death sentences for stealing chocolate in the last days of the war. Then there was The Golden Plague (1954), a film noir which visualized gold-digging small town Germans exploiting American G.I’s stationed there, while simultaneously employing anti-Semitic stereotypes to turn the former perpetrators into victims. The film’s mixed messages may be due to the fact that the film was written by the author of one of the most virulently anti-Semitic novels published during the Third Reich, while being directed by John Brahm, a German Jewish exile returning from Hollywood. And as I noted in my talk, of the more than 500 German émigrés to Hollywood, less than 20% returned to Germany after the war, and they remained completely invisible, so as to avoid anti-Semitic reprisals.

Possibly the greatest irony of the symposium, however, was its location in the former IG Farben complex, given that the chemical giant held a controlling interest in the production of Zyklon B for the Nazi gas chambers.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation