The New York Times reported last week that Andrew Sarris, long-time film critic for the Village Voice, had died at the age of 83 in Manhattan. Sarris had a huge influence on academic film studies, because he was the first American film critic to apply theoretical principles to his film criticism. At a time when most critics still preferred impressionistic viewing, his auteur theory looked at American cinema as a film director’s art form, which elevated previously neglected American auteurs—like John Ford, Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock—to the level of European filmmakers. The “theory” had been imported from France, where directors were considered gods on the set, but not everyone agreed it was applicable to the industrial production process in Hollywood; the ensuing critical wars between Sarris and Pauline Kael and/or John Simon became legendary. With a Voice subscription, I read Sarris’ column religiously.

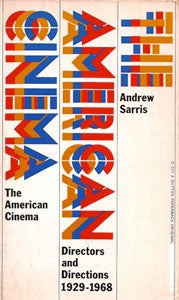

Sarris’ magnum opus, "The American Cinema: Directors and Directions," 1929-1968, was one of the first film books I ever bought as an undergraduate and for a couple of years it was my bible. After becoming the film critic for my college newspaper, The Review, I proudly declared myself an auteurist. As I developed as a film scholar, my critical faculties became more nuanced, but Sarris’ book still holds up surprisingly well in its short, pithy analyses of the work of individual directors, even if his multi-tiered levels of critical value from the pantheon (the greatest) to “less than meets the eye,” was a bit too pat.

In the fall of my senior year at the University of Delaware, I actually got to meet Sarris when our film professor, Gerald Barrett, invited him to campus. I described the lecture in a piece, noting (which I had completely forgotten) that Sarris railed against many modern films: “Films no longer serve as vehicles of communication, rather they become 'heavy' artistic statements on the state of contemporary existence.” In other words Sarris was very much a classicist who wanted to recuperate the old Hollywood studio system. I sent Sarris my little article and soon after, I began an occasional correspondence with Sarris, and he became somewhat of a mentor to me.

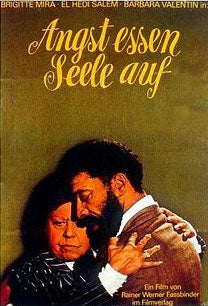

A year into graduate school at Boston University, I spent the summer in Germany researching my thesis and I saw Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974). I wrote an article, since I knew the film hadn’t opened in America yet, and sent it to Andrew Sarris. Much to my surprise, I opened the Voice in October 1974 and found my review starring at me. It was my first published piece in a non-student publication and earned me $75. More importantly, it gave me the confidence to pursue a film career when my parents were lobbying heavily for me to look for something more respectable.

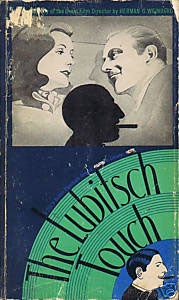

Sarris next gave me some good advice. While in Germany doing my master’s research on Ernst Lubitsch’s German career, I had discovered that significant portions of Herman Weinberg’s classic monograph, "The Lubitsch Touch" (1968), had been translated and reproduced without credit from a German language book on the history of UFA. Being a young, passionate film scholar, I was naturally incensed at this blatant case of plagiarism and set about putting together an article comparing the appropriate passages from both the German and English text. I sent my text to a couple of publications, including Sight & Sound, only to have it quickly rejected. Penelope Houston wrote that they couldn’t publish such material. I eventually sent the piece to Sarris and asked for his comments.

Sarris wrote me a very nice response, saying that he was sure my findings were probably correct, but suggested I drop the matter. He pointed out that Weinberg was so well-known and powerful in film circles and that “You may not have the stomach for the kind of nasty counterattack he might mount against you.” In other words, he could probably do 10 times more damage to my budding career than I with this exposé could ever do to his. I took Sarris’ advice and maybe saved my career, because word did eventually get back to Mr. Weinberg. The next revised edition of "The Lubitsch Touch" (1977) included a note stating that passage from Lubitsch’s early career had been translated by an independent researcher.

More than a decade later, after becoming the film curator at Eastman House, I ran into Sarris at a film screening in New York and thanked him again for his generous help. He smiled ambiguously. Having since been in similar situations where strangers thanked me for something I supposedly did for them, I’m sure he remembered nothing.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation