Recently, at a dinner with Todd Haynes and B. Ruby Rich, we were discussing Douglas Sirk, the German American film director whose melodramas with Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman were such a huge influence on both Haynes and R.W. Fassbinder. I mentioned my visits to Sirk in the late 1970s, when he was living in Switzerland, about 30 miles from my parents' home and they said I had to write up my memories.

In fall of 1976, I had just completed a one year internship at George Eastman House and an oral history project funded through the Louis B. Mayer Foundation on German Jewish émigrés to Hollywood. While visiting my parents, I decided without much of an introduction to call Mr. Sirk. To my surprise, I was immediately invited to afternoon tea at their modern flat in Ruvigliana, high above Lake Lugano. In order to prepare for the interview, I reread Jon Halliday’s interview monograph, Sirk on Sirk (1972), and prepared a bunch of questions.

I was met by Sirk and his wife, Hilde, and we sat down on his balcony with its gorgeous view. He wouldn’t let me use a tape recorder, but my notes from that first meeting indicate that we talked only briefly about his own career; rather, we discussed many of the people he knew, like Bertold Brecht, Erich Maria Remarque (who happened to be buried just across the lake) and actor Fritz Kortner. Sirk was incredibly modest, given his towering achievements at Universal in the 1950s, and didn’t really want to talk about himself, other than to say that he had left a promising career at UFA because of his Jewish wife. He also mentioned another émigré, Rudolph Joseph, who had been his production manager on his first films in Hollywood. Rudi had become the founder of the Munich Filmmuseum in 1963 and I met him a short time later. Little did I know then that not quite 20 years later, I would become Joseph’s indirect successor in Munich.

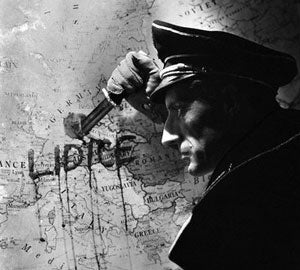

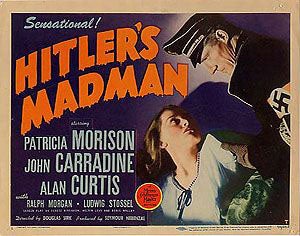

Over the next several years, we exchanged phone calls and Sirk always sent me a holiday card. We met again in September 1979, by which time I had become a doctoral candidate and was writing a dissertation about anti-Nazi films made in Hollywood by German émigrés. One of the most important films in my project was Sirk’s first Hollywood feature, Hitler’s Madman (1943), which is a fictionalized version of the assassination of the Nazi “Protector” of Bohemia, Reinhard Heydrich, by Czech patriots, and the horrific destruction and mass murder of the entire Czech village of Lidice in retaliation. I was particularly interested in this film, because Fritz Lang and a another group of émigrés made Hangman Also Die (1943) about the same events. Furthermore, my great aunt had briefly hidden one of the assassins, my dad had been in the Czech underground, and I had visited the Lidice memorial as a teenager in the 1960s. When news of Lidice spread around the world in early June 1942, Sirk was working a chicken farm in the San Fernando Valley, waiting for a chance to direct in Hollywood. Asked about the film, Sirk told me: “You can’t imagine how shocked people were in this country. Given that many Americans still sympathized with the Germans, Lidice made this country realize that the Nazis were animals. For the German émigrés, it meant they could never go back to Germany.”

Sirk said he made the film on no budget, working with a fellow émigré producer, Seymour Nebenzahl, then sold the film to MGM, where some scenes with John Carradine (as Heydrich) were reshot to give the film better production values. In contrast to his low opinion when he had been interviewed by Halliday, Sirk had seen the film again recently and was surprised at how good it was. It had been his idea to include the poem by Edna Vincent St. Mallay, when the men of the village are executed, and he was still proud of that insertion.

Sirk was a very literate man. We had a long talk about William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, two of his favorite authors. At the time, Sirk had just returned to directing and adapting Williams for three short films, produced with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and others at the Munich Film Academy. He said he did it for the students, who made up the film crew. Sirk also told me he had never looked back after leaving Hollywood at the absolute height of his career in 1960. Gazing at Lake Lugano and the setting sun, I understood why.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation