The annual Congress of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) usually starts with a two day symposium on some subject of interest to the delegates from as many as 160 different countries. This year’s symposium, organized by the China Film Archive in Beijing on April 22 and 23 considered the history and preservation of animation. On the first day there were a variety of speakers, including Japanese, French and Chinese animation specialists. The keynote was delivered by the director of the Tokyo Film Center, Mr. Hisashi Okajima, who gave an impassioned talk about his childhood love affair with animation, both in the cinema and on television.

Jez Stewart, the animation curator at the British Film Institute in London reported on the BFI’s acquisition of the massive Bachelor and Halas Collection. John Halas was a Hungarian animator who emigrated to Britain just prior to World War II, then married fellow animator Joy Bachelor. Best known for their feature, Animal Farm (1954), the Halas & Bachelor studio created over 2,000 animated films for commercials, industrials, television and experimental films. The daughter has now donated all the papers and films to the London archive and they are in the process of cataloguing and assessing the collection. My ears pricked up, because I know Saul Bass also worked with Halas & Bachelor.

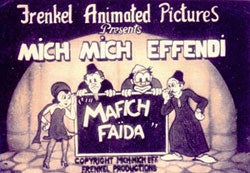

I was also particularly interested in Eric LeRoy's talk. The Director of the French Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée introduced the Frenkel Brothers from Cairo, who apparently in the 1930s and 1940s made a whole series of cartoons with an Egyptian character named Mish Mish Effendi. David, Solomon and Herschel Frenkel had emigrated from Belorussia to Jaffa with their parents, and then to Cairo, where they operated a successful furniture factory turning out antique Chinese lacquered cabinets by day, and drawing animated films at night. Mafish Fayda opened in February 1936 and began a successful series with Mish Mish that resembled the Fleischer Brothers animation style, but with plenty of local color. They then emigrated to France in 1951, after the Palestine war of 1948 made it impossible to stay in Cairo, and continued to produce animated films in the 1950s, completing their final film, Dream of the Blue Danube, in 1964.

Another Japanese speaker, Akira Tochigi, spoke of Japanese animation in the 1930s, which was a precursor to modern anime. In the evening we went to a screening where we actually got to see a bunch of these Japanese films and I certainly saw how the “Hello Kitty” aesthetic originated. My particular favorite was The Spider and the Tulip (1933), which was a very cute cat-and-mouse game between a spider (unfortunately in blackface) and a cute little ladybug who doesn’t want to end up as lunch. But the real surprise of the evening screenings were the Chinese animated films by Te Wei, which were wonderfully lyrical, incorporating traditional Chinese bamboo painting into their style. Both Ju Di (1963), about a boy playing a flute on a water buffalo and an earlier film about tadpoles looking for their mother, Where’s Mama (1960), had an amazing sense of nature, despite the simplicity of the animation.

The second day of the FIAF Symposium was not quite as interesting as the first—except of course for Mark Quigley's very well-organized presentation on UCLA Film & Television Archive’s silent film animation webpage—but still very worthwhile. Mark had his challenges, because the Chinese internet wouldn't actually let him access the webpage—VERBOTEN—but he managed well with frame grabs. My favorite presentation of the day was by two archivists from the Polish National Archives in Warsaw, Tadeusz Kowalski and Elzbieta Wysocka, who presented the animated films of Julian Jozef Antonisz. In the 1960s and 1970s he made cameraless animated films by drawing on clear film leader, scratching images on the film, filling in the scratches with shoe polish, then hand coloring (his wife did that). In order to make the process more efficient, he invented a machine that would allow him to draw on a regular piece of frame and an arm would scratch the same image on 24 separate frames at the same time. The kicker was this "machine" was patched together out of old nails, balsa wood and other metal scraps he found on the street since he was not supported by the state (these were communist times) and had no money. The Poles are preserving the contraptions along with the films, which are being digitized.

Victor de Fochts from the Royal Belgian Film Archive also contributed an interesting talk on the origins of Belgian animation, including Tintin, which turns out to be a very popular comic book series, long before Spielberg. And there were two presentations on Emile Reynaud and Jacque Demeney, two French pre-cinema pioneers, with both speakers arguing that animation predates cinema and film should therefore be considered a subset of animation and not vice versa.

There were also film screenings every night for the a whole week of the Congress, which were extremely well attended by very young Chinese audiences, but unfortunately other Congress business kept me away.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation