It never occurred to me that after our great adventure last fall with “L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema,” I would be writing this kind of blog so soon after. It is with deep sadness that I have to announce the passing of our brother, Jamaa Fanaka, on April 1, 2012. Jamaa was a bigger than life person who did not always stick to the script that others had written for him, but he had a huge heart and became a wonderful friend to all of us working on the L.A. Rebellion project.

Through the process of putting together that show, Jamaa and I became good friends, “Friends For Life,” as he liked to say. Always attentive, he would call me at home on any and all holidays to wish me the best, and, during our many conversations, he would sometimes intimate that he was not long for this world; I never took that quite seriously, because he seemed, apart from his diabetes, so full of life.

We first met a little more than two years ago, when the Archive contacted Jamaa to see whether he would place his films at UCLA as part of the L.A. Rebellion collection. I wrote a blog about that encounter, the first of many about the Rebellion project. However, we really bonded in the summer of 2010, when Tony Best, Jackie Stewart and I spent two whole days with Jamaa, cleaning out a shed in Compton that held all his films and papers. We found the only surviving print of his first film, A Day in the Life of Willy Faust, or Death on the Installment Plan, at the very back and bottom of the storage unit. His papers, which several graduate students have since organized in archival boxes and catalogued, were collected as loose leafs in garbage bags. Happily, his artistic legacy is now in order.

There were those, even among his colleagues at the Rebellion, who thought that Jamaa played the fool. But Walter Gordon was no fool. Indeed, coming out of the Air Force, he figured out how to avoid the many traps facing an African American male at that time, and get ahead. It took more than a big, brash mouth to make three 35mm feature films before he graduated from UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. That record has yet to be broken.

"I like to think of Jamaa as the trickster of the L.A. Rebellion group. He came from a middle class family, but liked to affect a streetwise, homie attitude, throwing out double entendres and clever quips, like some rapper on the run. Jamaa loved to live and think large..."

I like to think of Jamaa as the trickster of the L.A. Rebellion group. He came from a middle class family, but liked to affect a streetwise, homie attitude, throwing out double entendres and clever quips, like some rapper on the run. Jamaa loved to live and think large, even when economic circumstances had reduced him to modest means. Yes, he loved to be the center of attention, yes, his stories would sometime go on too long, but he could weave a tale that kept you at the edge of your seat, even when you were afraid he was getting perilously close to bad taste or a faux pas, then at the last moment he would pull back to what was his original, often brilliant point.

He was also anything but a trickster in terms of his personal relations. I don’t think there would have been anything he wouldn’t do for you if he could. He also never spoke badly of anyone, always looking with humor for what was good in a person, always supporting his colleagues, because, he said, there was room at the top for all of them.

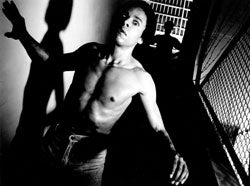

Of all the L.A. Rebellion filmmakers, Jamaa was the most commercially successful, maybe because his films at least on the surface seemed to conform to Hollywood conventions. Penitentiary earned millions, riding the last wave of the so-called "blaxpoitation" era. That moniker bothered Jamaa, because he really saw his work not as exploitation, but as his own personal form of independent cinema. At the same time, some of his colleagues thought Jamaa’s films an anomaly within the Rebellion, which prided itself on existing far from Hollywood. Happily, I think we did our part to demonstrate how, within its diversity, the Rebellion was of a piece, embracing many forms, including the unique work of Jamaa Fanaka.

For me, his Willy Faust, the three Penitentiary films, Emma Mae, Brother Charles and Street Wars are unique expressions of a filmmaker who never strayed far from his own community, who used humor and sometimes outrageous hyperbole to get our attention and make a point while also entertaining us. Interestingly, too, Jamaa’s films are almost always about family: families in creation, in dissolution, or non-traditional families, like the prison inmates.

In the spirit of the Rebellion, Jamaa was also an activist who cared about improving the lot of others in the community. The unkind obituary published by Variety this week harps on his lawsuits against the Director’s Guild of America and the major Hollywood studios and makes him sound like a crank. In point of fact, Jamaa was fighting the good fight against what remains to this day the shameful race politics of the major entertainment companies, in terms of hiring behind-the-camera talent and producing stories with any sort of color, and I’m not talking about Technicolor. But Jamaa struggled alone—after his allies had deserted him—studying the law and supplying his own counsel against big finance, corporate lawyers, a Don Quixote railing against windmills he could never hope to defeat.

Jamaa, FFL, I will miss you. I’m saddened by the fact that you won’t be able to see your films reach new audiences on our L.A. Rebellion national tour, but very happy you were able to share so many precious moments with us last fall. Farewell, Brother.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation