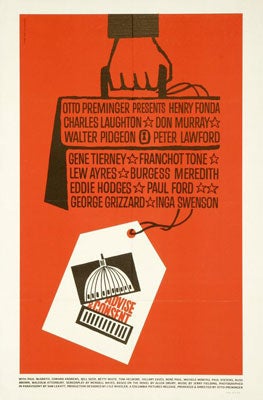

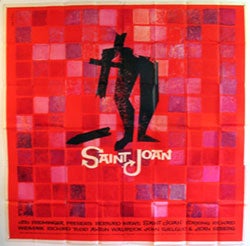

I first became aware of Saul Bass in the early 1990s. Through my work as curator at George Eastman House, I had met various film poster dealers at collector conventions, like the Syracuse Cinefest and (now L.A. based) Cinecon. I soon started buying an occasional poster, because what struck me about the Saul Bass work was how utterly different it was from the run-of-the-mill movie poster, their striking graphic design, their simplicity. One of the first I acquired was for Otto Preminger’s Advise & Consent (1962), mainly because I got a great deal from a friend, but also because of its witty visual trope. Even back then, prices for his movie posters were starting to climb to levels well beyond my budget. Today, most Bass posters sell for north of $1,000 and some like Vertigo (1958) or Saint Joan (1957), will likely cost more than $2,000.

In 1996, I was invited to program a Weimar German avant-garde film series for the Aspen International Design Conference, which Bass had attended regularly. In that year of his death, the conference presented a memorial event, which included examples of his short film work, as well as slides of his corporate identity campaigns for AT&T and other major American corporations. It was then that I realized that there was more than a passing connection between my own previous research on the Bauhaus and the German avant-garde, and Saul Bass.

Jump cut to 2002, when I was earning my living cobbling together exhibitions at a rate of eight a year, with zero budgets, for a disreputable operation called the Hollywood Entertainment Museum, now happily defunct. Most of my shows were begged, borrowed and stolen from collector and dealer friends and so it was with “Saul Bass: Designer,” which opened in February. Thanks, to a well-known L.A. designer, Augustine Garza, who had been a student of Bass’, we organized an evening for former students, where I learned just how much the man had been revered. I decided to do a book on Saul Bass, because amazingly there was none to be found.

Given my museum workload, though, that remained only an intention until I entered a period of full unemployment, when I began initial research on Bass, accelerated in early 2007 after I was named an Academy Film Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. I quickly learned that Bass had studied with Gyorgy Kepes at Brooklyn College, himself a student at the Bauhaus of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the subject of an essay I had published. A thesis began forming in my head. The Academy honor began my Hollywood comeback, culminating at year’s end with my appointment as Director of UCLA Film & Television Archive, but also bringing my Bass research to a screeching halt.

It wasn’t until three years later that I felt comfortable enough in my job to begin research again. In the winter of 2011, I was granted a very smart research assistant, Alexandra Schroeder, who started systematically looking at the Bass estate papers at the Margaret Herrick Library, and I followed suit in the summer, viewing the newly available Bass film collection, thanks to the help of Mae Huadong, a former UCLA student of mine, now working at the Academy Film Archive. I was still hesitant to start writing, though, because I knew a book on Saul Bass to be published by Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham had been looming on the horizon for more than a decade. I was particularly concerned about the biographical details of Bass’ life, since my research indicated that Bass had engaged in no small degree of myth-making.

When "Saul Bass: A Life in Design and Film" (London: Laurence King Publishing) finally appeared in December, it turned out to be a beautiful, large format, coffee table book with a huge amount of both visual and biographical documentation, but also left plenty of room for the work I was planning. I was elated and energized, knocking out a complete outline of my Saul Bass book the day after Christmas and starting to write a day later. I’ve now knocked out over 80 pages of the manuscript, while I continue to do research, entering a kind of euphoric obsessive state that I recognize from the hot phase of my dissertation and subsequent book projects. Much of that feeling has to do with the thrill of the hunt, chasing down obscure bibliographic sources in libraries, finding new details in the Bass papers (thanks to Academy archivists Jenny Romero and Barbara Hall) and making intellectual connections that previously didn’t exist. But it also has to do with the fact that I’ve become more and more convinced that Saul Bass is a subject worthy of attention, justifiably famous among cognicenti, but also strangely invisible in most auteur-centric film histories. I want to change that. For me as an archivist and historian, there is no goal more worthwhile.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation