Screen is one of the most venerated journals of Anglo-American film studies. Founded in 1959 as Screen Education by the British Film Institute, it was renamed Screen in January 1969. With the name change came a theoretical turn away from adult education to film theory. Indeed, over the next 15 years, Screen became the bastion of structuralist, post-structuralist and psychoanalytic film theory, the most intellectual and influential of all film publications in the 1970s, especially because of its reception and promulgation of French theorists such as Jacques Lacan, Christian Metz, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. Over the past 20 years, Screen has also organized an annual conference, which has likewise often been agenda setting for the field of film studies.

This year, I was invited to give a keynote speech, although I had never previously attended a conference and am not exactly known for my film theoretical work. But then, this year’s topic in the call for papers was “repositioning screen history,” with the sub-topics “issues of preservation and restoration,” and “archival theories and practices.” Other keynote speakers were Barbara Klinger, who spoke about the continued afterlife of classic Hollywood films like Casablanca and Gone With the Wind, Christine Geraghty on the dichotomy between close textual analysis and contextual analysis, and Mark Betz (my former student from Rochester, now a Professor at Kings College, London!), who argued that the differences between European art and exploitation cinema were not that great and we need to rethink categories. Given that over a two-day period almost 100 papers were presented in six concurring sessions, I could only attend a small number of talks, and therefore focused mostly on archival issues.

Most germane were two papers by Liz Greene and Liz Watkins on a panel I was asked to chair. They discussed the recent digital restoration by the British Film Institute of The Great White Silence (1924), one of a number of films edited by Herbert G. Ponting from his documentary footage of the ill-fated 1912 Scott expedition to the South Pole—with 90 Degrees South (1933) being the better known, sonorized version. Greene produced a fantastic flowchart to document all the various sources used by the preservationists, wherein I learned that the new version has added digital tinting and toning—based on French and Dutch video prints—even though the surviving nitrate print of the English version was black and white. How do you establish authentic color from video references? I asked.

Next, Greene presented a very interesting paper, based on her dissertation, on the sound archive of the late sound designer Alan Splet and his wife Anne Kroeber, who worked on all of David Lynch’s films through the early 1990s, but also for Carroll Ballard, Philip Kaufman and Peter Weir. After Splet's death, that valuable archive is unfortunately now at risk.

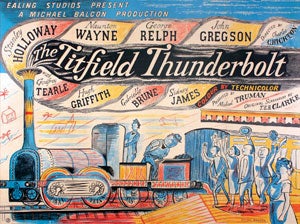

Another very interesting panel, “Cinema as Archive,” attempted to reconceptualize the very notion of the archive. Using the recent Sherlock Holmes (2009) as a case study, Constance Balides noted the way digitality has allowed Hollywood filmmakers to insert documents and images directly into their historical narratives, increasing their surface veracity. Rebecca Harrison, on the other hand, discussed the great Ealing comedy, Titfield Thunderbolt (1953), as itself an archive of objects, facts and phenomena surrounding the demise of local, small gauge railroads in mid-century Britain. Looking at early French ethnographic films made before 1915, Katherine Groo theorized that these unformed, often unedited documents from the archive were essentially incoherent, relying on written, scientific accounts to accrue meaning. Finally, Wendy Haslem discussed the installations of the American artists Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, who among many other works have created faux archives and nonsense taxonomies by “cataloging,” for example, every “yellow VW,” “tornado spin,” or “fall from a great height” from 100 different “Looney Toons” cartoons.

Another panel, chaired by my German colleague Jan Distelmeyer, offered Dagmar Brunow discussing the difficult preservation issues surrounding the work of independent Hamburg-based video-film collectives in the 1970s, given that formats such as Sony Portapak (quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape) are extremely fragile, on the one hand, and that these collectives came out of an anarchist and anti-government ideology and still loathe to accept government money for preservation, on the other. I was also intrigued by Iain Robert Smith’s research on illegal, file-sharing websites that use BitTorrent technology, like Cinemageddon and Karagarga, to “distribute” exploitation films that are not available commercially in any format. Smith argues that these “bootleg archives” are in fact essential for academic researchers mining the lower depths of schlock cinema, whether from Turkey, the Philippines or Mexico.

Finally, there were a lot of papers I didn’t get to because there wasn’t time but should have, including Charlotte Crofts on a new app to explore the Curzon Collection of historic film projectors; Celia Nicholls on Henri Langlois and the Commission de Recherche Historique, and Justin Smith on a digitization project to make the weekly information packets of Britain’s Channel 4 television accessible to researchers.

My keynote took the audience from the Elysian Fields of high theory to the lower depths of rude archival practice, discussing the paradigm shift to digital archives and the problems and pitfalls that such a transition from analog has entailed. The extreme fragility of digital media shocked none too few of these mostly U.K.-based film academics, who thought their DVDs and Blu-rays would last, if not forever, then at least until they retired.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation