I don’t know when I first went to Syracuse for Cinefest, an annual, four-day weekend convention of film collectors and fans of old movies. The event includes a market for memorabilia and 16mm screenings at a local hotel from 9 a.m. to 12:30 a.m., as well as 35mm screenings on Saturday at a local cinema, this year at the Palace in North Syracuse. Almost none of the films are available on television or video and none were made after 1940. Indeed, many of the screened prints are in the hands of collectors, making Cinefest also a destination for film archivists in search of lost treasures.

I think it was 1988, when Phil Serling the late founder of Cinefest, first invited me to a different kind of March madness. At the time, I had just assumed the position of Senior Curator of Film at George Eastman House in Rochester, and had the privilege of meeting many of the first generation of great film collectors, including Phil Serling himself, William K. Everson, Alex and Richard Gorden, Phil Berkow, Ray Regis and many others now gone. Back then, the relationship between archivists and collectors was somewhat contentious, because we professionals were perceived by collectors to be hoarding treasures, while some archivists believed collectors to be film pirates. Needless to say, it caused a stir when I began attending Cinefest regularly. These days, the Syracuse Cinephile Society—lead by Gerry Orlando, Bob Olive, Terry and Margaret Hoover, Ricky Scheckman, Joe Yranski, and Andy and Lois Eggers—continues the tradition, and archivists and collectors buried the hatchet long ago in the interest of their mutual love of old movies.

This year’s Cinefest 31 ran from March 17-20 and included none too few discoveries for this writer. The first was Forgotten Commandments (1932), which repurposed the spectacular Moses footage, including the parting of the Red Sea, from Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923) to construct a morality tale about the “godless” Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. Surprisingly well-made by Paramount, the film does have an ideological problem in that the commissars are better looking and certainly smarter than the god-fearing peasants they are oppressing.

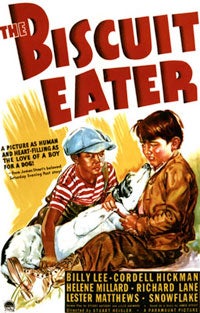

Mannequin (1926), directed by James Cruze and starring Zasu Pitts and Dolores Costello, was also a surprise, dealing with a mentally unbalanced nursemaid kidnapping a child, in part because the well-to-do mother is a shopaholic. The Biscuit Eater (1940), directed by the unsung Stuart Heisler, was an amazingly unsentimental kid’s flick about a boy and his dog in rural Georgia that also realistically depicted the not uncomplicated race relations between blacks and whites in the post Reconstruction South. Wolf Song (1929), a late silent, featured a vey young Gary Cooper in the buff as a wandering mountain man and Lupe Velez as the erotic Mexican señorita who finally domesticates him. The Woman and the Puppet (1920), based on the same Pierre Louÿs novel that Josef von Sternberg would turn into Devil is a Woman (1935), starred Geraldine Farrar as a gypsy-cum-dominatrix in a totally sadomasochistic relationship with a Spanish Don.

Even more shocking was the pre-Code film The Story of Temple Drake (1932), starring Miriam Hopkins as a rape victim who is kidnapped and willingly lives in a house of prostitution with her attacker. Today we understand the pathology of this “Patty Hearst syndrome,” which also characterizes relationships between underage prostitutes and their pimps, but at the time the film caused Joe Breen of the Hays Code to ban the film. Finally, on the lighter side, Lessons in Love (1921), starred the always wonderful Constance Talmadge as an heiress who must marry for money and masquerades as her own maid to test the would-be groom: S & M light.

For the less adventuresome, there were also certified classics like Lonesome (1929), What Price Glory (1926) and Music in the Air (1934), and for my money, Cinefest 31 did not disappoint in uncovering Hollywood’s less formulaic fare.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments